Published in the Overland Sunday, 14 March, 2021.

By Lizzie O’Shea, Rebecca Giblin, Kate Seear and Alexandra Dane.

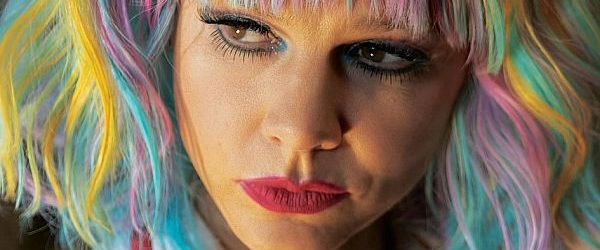

Promising Young Woman boldly examines male entitlement and female rage from a woman’s perspective. By which we mean: it’s not simply a story about a woman, but a story told through a female gaze. That shift in perspective makes it a radically different, distinctive treatment of these topics. If you haven’t seen it, you should, especially before reading this essay. It contains spoilers.

Promising Young Woman exemplifies what has become a truism of modern life: that every woman knows a woman who has been raped, but no men seem to know any rapists. It asks how you can live as a woman in a world where female potential is sacrificed regularly and carelessly at the altar of male entitlement. This culture is found in workplaces, universities, boardrooms, factories and – as we’ve been so painfully reminded over the last few weeks – Australia’s Federal Parliament.

The film’s protagonist, Cassie, is tormented by the rape of her lifelong best friend Nina by fellow medical school students. This violation derailed Nina’s prospects and ultimately claimed her life. A one-woman vigilante, Cassie ends up losing her own to exact revenge for Nina, a sacrifice made out of platonic love. Although this is a story about two women, Nina serves as an emblem for generations of women pushed out of positions of influence and power, while Cassie represents the multitude of enraged women who have hoped for change, and for justice, but found neither.

Promising Young Woman has its limitations and some of the execution is clumsy, all of which give rise to legitimate criticism. However, as women around the world gather to march, we could not let this moment pass without challenging some of the criticism which we feel misses the central point – and, by extension, the reason why women’s rage is again bubbling towards boiling point.

We’re thinking, specifically, of Christos Tsiolkas’ review in The Saturday Paper, which laments the film’s ‘lack of courage’. Disappointed that Promising Young Woman does not acknowledge what he sees as the obviously Sapphic nature of Nina and Cassie’s relationship, Tsiolkas concludes that in

the narrow worldview of this film, there is no happiness in adulthood, there is no sexuality that is liberating for a woman. The only choice is between perpetual girlhood or violent martyrdom.

The review came out weeks ago, but every heart-rending revelation to have come out of Canberra since means that this review keeps returning to the front of our minds. Because Tsiolkas, like so many male commentators responding to those new allegations, seems unable to grasp the female perspective, and thus fundamentally misapprehends the source of our despairing, cumulative rage, and the conditions necessary to move beyond it.

Take, for instance, his claim that the ‘ferocity of [Cassie’s] grief’ makes it feel ‘improbable that no-one around her names the relationship as one of lesbian love’. In what world is sexuality the sole impetus for women’s rage? A man’s world. Tsiolkas is far from the only man to mistakenly assume women who care deeply for one another must be boning, and that’s a critical blind spot in men’s understanding of women’s anger. Women’s friendships can run deep and pure and fierce. In 2017, the #MeToo movement showed us that our own experiences weren’t isolated, and that everything that had been done to us had also been done to the women we love. That understanding was central to the power it unleashed. It has surely also driven much of the rage Australian women have felt anew in recent weeks.

Against that backdrop, we see the film’s central question very differently: how do you navigate a world in which female potential and dignity are exploited and destroyed for the sake of male entitlement, when its every structure and institution has been constructed by the white colonial patriarchy to preserve its own power? If that’s the question being asked, Cassie is driven by an undeniable logic (albeit to the point of obsession). Indeed, it’s a question so many of us are asking, after devoting so much effort to fighting this system with apparently fruitless effect. What can we do when men just keep getting away with it?

Tsiolkas also laments the ‘fetishising of victimhood and suffering’ that he sees as a hallmark of ‘contemporary progressive politics’ and the film’s apparent ‘injunction to remain soldered to the traumas of one’s past’. Thoughtful works have been written on contemporary notions of victimhood and on the politics of suffering and trauma, such as Laura Kipnis’ provocative Unwanted Advances: Sexual Paranoia Comes to Campus. But there are a multitude of problems here with Tsiolkas’ analysis.

Women’s victimhood and suffering are rarely fetishised in the ways Tsiolkas claims. If anything, they are routinely dismissed, instantiated as disordered, irrational, dysfunctional, pathological, obsessive and delusional, rather than righteous and rational. Worse, Tsiolkas ties Cassie’s apparent dysfunction and perpetual victimhood to her closeted sexuality and refusal to grow up. We could pathologise women’s victimhood, or we could see that victimhood as a reflection of deeply entrenched social, cultural and institutional dysfunctions. Women who remain soldered to the traumas of their past do so for numerous, complex reasons, including institutional failings, endemic failures to hold perpetrators to account, the ongoing trivialisation of sexual assault and abuse, and gaslighting. Tsiolkas reads Cassie’s obsession with the past as pathological, rather than evidence of the social pathology that has produced it.

Cassie gives those responsible for Nina’s death opportunities to do better. The choice she ultimately makes, and one that sits at the heart of this film, isn’t between perpetual girlhood or violent martyrdom – it’s between personal sacrifice and systemic change. But change only happens when it causes less pain than leaving things as they are. The patriarchy has not yet been pushed to that point, but growing numbers of us are prepared to help it get there. And we’ll be out together in force, fierce and angry, marching for ourselves and for the women we love.

The Women’s March 4 Justice takes place across the country on 15 March 2021 (except for Cairns and Perth, that will hold their events on Sunday – full details here). Come along with black clothes and masks.