The Facebook scandal shows that the rules of the internet need to be written by ordinary people, not corporations

Facebook’s reckless vanity has made the headlines again, with the revelation that data it held on about 50 million users was exploited commercially without their consent, and that when Facebook found out about this, it did pathetically little. We only know this thanks to the bravery of a whistleblower. This is yet another scandal in a troubled period for the company, with a growing sense that it is all profit, no responsibility. But the current malaise goes wider than Facebook. On the internet more widely, the advertising-supported model has demanded its payout, and as a result our experience of the web is getting worse. Like rats scrambling to get back on a sinking ship, senior former-Facebookers are lining up to express regrets. It all feels too little, too late.

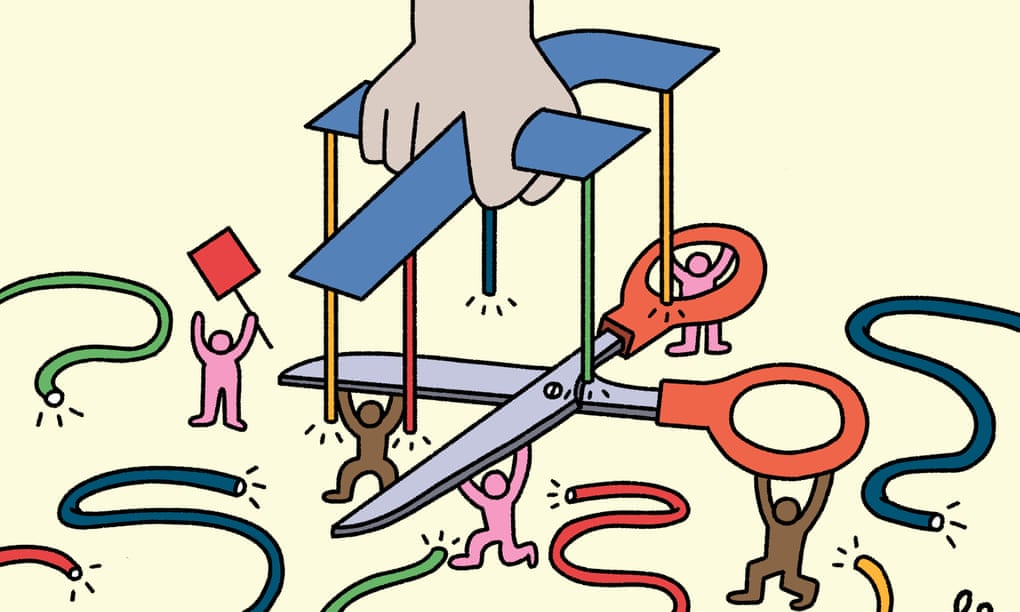

The problem of large corporations posing a threat to democracy is an old one. Monopolies that vest control of markets in a single person create “a kingly prerogative, inconsistent with our form of government”, declared US senator John Sherman in 1890, when he introduced his eponymous act, which became the cornerstone of American competition law. Facebook looks increasingly like digital royalty, and not in a good way. It controls vast amounts of our data and curates what we read with a mysterious and mercurial flair. As the Cambridge Analytica files show, the platform appears to prioritise advertisers over users, and doesn’t do enough to control how the data it collects is handled by third parties. Of course, Facebook is not the only offender: Amazon and Google have enough fingers in enough pies to make digital oligarchies a problem we can no longer ignore. But what is to be done? How could we make a platform such as Facebook less autocratic?

In the first place, it is critical that we understand this as a systemic problem with the business model. With that in mind, we could follow Sherman’s example and break up the market using anti-trust laws. But there are also ways to create alternatives from the bottom up. Governments and regulators could foster the conditions in which alternative networks with more democratic foundations could flourish.

One way to do this is to increase transparency and public participation around rule-making for digital platforms. For an example of what this means, we can look to Wikipedia. It has its problems, but it is a remarkable example of how to make decisions as a community, rather than a company. The method by which articles on Wikipedia are produced is governed by a set of rules that have been determined collectively, over time. There are arguments, there is consensus, and there is everything in between – all of which is documented for anyone to see.

Compare this with Facebook’s decree that its news feed would prioritise personal stories over media content, without any apparent indication that it considered the impact on journalism. Or its equally clunky attempt to survey users about who should decide whether child-grooming content should be permitted on the platform.

The Facebook executive team is clearly unaccustomed to managing democratic processes and genuine community collaboration. But it is possible to imagine a social network where users have a say in how, for example, our daily news feed is curated, and where each choice we make isn’t used by some tech giant as an opportunity to monetise our data. We need to start collaborating on the design of rules, create a culture of transparency among platforms and have discussions about what constitutes the public good. It is often said that the spaces for discussion created by social media companies are the 21st-century equivalent of the town square or public meeting. We cannot continue to leave the decisions about how to organise these to the private sector.

If we want to create alternative services and give them a chance to grow, we will need ambitious programmes of public investment. Platforms organised around the public good will need to be resourced to build a user base, and it is time we stopped pretending that venture capitalists are any kind of proper substitute for public money and oversight. There are precedents for this. Minitel in France, for example, is often scoffed at in Silicon Valley, but actually worked pretty well. Minitel was a publicly supported informatics system before the modern internet, and boomed thanks to government investment. Anyone with a French telephone line could get a Minitel monitor for free and make use of the hybrid public-private network between the late 1970s and 1990s. It looked a bit like a government information service and a bit like Craigslist, where people could access information, buy things and hang out in chatrooms without anyone using these as data farms for black-ops marketing.

We have many good reasons to be wary of governments controlling the internet. But investment in infrastructure does not have to be synonymous with state spying. Interestingly, Minitel was built in such a way that users retained a form of anonymity. There was a central money-collecting service (a bit like how the Apple store today sells books, music and streaming services). But service providers were never given an itemised bill, so they did not know who their users were.

Minitel was still centralised, however: all communications had to go through one node. So while we can learn from its example, we also need to allow people to communicate and collaborate without replicating this weakness. What this means is a return to the days before the big tech companies and spooks oversaw the concentration of web activity through central nodes. The internet began as a decentralised network, but market consolidation has effectively changed this, even if its technical underpinnings have remained unchanged. This is what pioneers including Sir Tim Berners-Lee mean when they talk about the need for a “re-decentralisation” of the web.

Modern technological capabilities mean that this objective is within our grasp. Projects such as Berners-Lee’s Solid offer a glimpse of what might be possible, by allowing people to control and port their data to different services. The blockchain also has the potential – well beyond cryptocurrencies – to help people deal with each other without having to rely on a centralised platform or ledger. We have the technical capacity to chat, cooperate and trade directly with each other, without relying on private platforms that measure value in ad revenue.

“The internet’s inherent value and power come from the fact that it is globally interoperable and decentralised,” writes the internet freedom advocate Rebecca MacKinnon. Everybody can add value to the network, without having to get permission. The basic technical protocols that allow this kind of collaboration are still in place, but the profit motive and market centralisation have undermined their effectiveness.

We need transparent and participatory approaches to rule making, public investment in digital infrastructure that does not facilitate state snooping, and decentralised forms of data management. Without these kinds of changes, we are unable fully to make use of the enormous resources generated by a network of billions of people. We also, as the news about Facebook has made frighteningly clear, risk undermining the democratic processes that hold wealth and privilege accountable.

View original article: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/mar/20/digital-oligarchs-rewire-web-facebook-scandal